The Anatomy of the

Golf Swing

Instructor Certification Manual

Level 1

First Edition

Chuck Quinton

With Al Consoli

ROTARY SWING GOLF INSTRUCTOR

CERTIFICATION MANUAL LEVEL 1. Copyright 2010 by Chuck Quinton. Published February 11, 2010. All rights

reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be

used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except

in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For

information, contact Quinton Holdings Corporation, PO Box 215, Gotha, FL 34734

or on the web at www.RotarySwing.com

FIRST EDITION

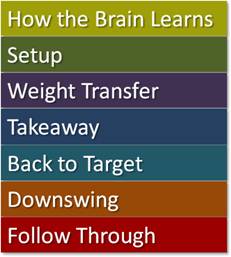

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: What is a Fundamental? 8

Chapter 2: How the Brain Learns 14

Chapter 3: Push vs. Pull 24

Chapter 4: In the Box 31

Chapter 5: The Grip 38

Chapter 6: Setup 47

Chapter 7: Weight Shift 66

Chapter 8: The Takeaway 72

Chapter 9: Completing the Backswing 89

Chapter 10: The Downswing 108

Chapter 11: Impact 122

Chapter 12: The Follow-through 127

Chapter 13: Ball Flight Laws

The golf swing is one of

the most complex athletic movements in all of sports due to the precision

required for successful ball striking. From a teachers perspective, it can be

almost an enigma watching a golfer with a terrible looking golf swing hit the

ball with power and control while a golfer with a beautiful swing struggles to

get the ball airborne. How does this happen, and how do you teach these two

students to improve? One instructor will have the student do one thing, and

another instructor will say the exact opposite. Is there not a set of

fundamentals in golf that everyone should use to learn to swing the club?

After all, there are fundamentals in everything else we learn in life.

Imagine picking up a saxophone for the first time and going to get lessons.

There is a specific way the instructor would show you how to hold the

instrument, how to blow, how to hold your posture, how to push the keys, etc.

And, if you went to see another instructor, theyd tell you basically the

exactly same thing. However, with the most complex and precise motion in all

of sport, you can rarely find two instructors that agree on anything, much less

a common set of fundamentals. Why?

The answer is actually

quite simple. Golf instruction has never been looked at exclusively from an

anatomic or scientific perspective. Many golf instructors, like a herd of wildebeests

running off a cliff, watch and blindly follow the top player of the era or their

favorite swing on tour and teach the golf swing based on how that player appears

to swing the club. How foolish is this? Common sense should tell you that

there are a million ways to successfully strike a golf ball, but would you go

and teach someone how to swing like Colin Montgomerie just because you liked

his swing? What about Jim Furyk? No one on the PGA Tour has a more consistent

path into impact that is more square through the hitting area than Furyk,

according to Trackman data. Shouldnt we then teach everyone to swing like

Furyk?

The truth is we as

instructors shouldnt teach students how to swing exactly like anyone presently

on the PGA Tour because no one swings 100% anatomically correctly yet. Tiger

Woods is admittedly the closest and continues to get closer. As of this

writing, he has altered his setup during the 2009 season to be less on the

balls of his feet, which as you will learn, will protect his hip, knee and back

during the rest of his career. But the truth of the matter is that even Tiger

is not perfect because he has either chosen to ignore the anatomical absolutes

of the body or simply isnt aware of the scientific evidence underlying what you

are about to learn. Im quite certain its the latter as Tiger wont be able

to deny or argue what you are about to read on the following pages because it

isnt based on opinion or preference, but medical and scientific fact.

For once, you are about to

learn that there are indeed a set of fundamentals in the golf swing, and for

once, you and your students will actually be rewarded for working on your golf

swings rather than ending up worse off than you started. We hope you enjoy the

process of discovery and learning and share it with all your students as they

will be the greatest benefactors of your Level 1 Rotary Swing Tour Instructor

Certification. Golf will be fun again, and you will understand the golf swing

like you never have before when finished with this course.

Chuck Quinton

Rotary Swing Founder

While this manual is

directed toward golf instruction professionals, the lay person will likely find

it extremely helpful as well. Some of the terminology is technical but well

established in the medical field, so for the sake of consistency, we use the

medical terms where appropriate. There is a glossary in the back of the book if

you come across a term that is unfamiliar. By the same token, some of the terms

have been simplified to make it more clear to the student what the goal of the

movement is. For instance, when we refer to the hands moving in a vertical

plane in front of the body during the backswing, the correct technical term

would be shoulder flexion. However, we are using the term shoulder

elevation to paint the picture that the arms/hands are being elevated by the

muscles in the shoulders.

Because the vast majority

of golfers in the world are right handed, the book is written in a way that

exclusively references the right-handed player. This is done to avoid the

cumbersome terminology of trailing hand, target side hip, etc. If you play

left-handed, you will need to simply transpose left and right.

This manual is written

first and foremost to educate the instructor on how to teach the Rotary Swing

Tour (RST), which is an objective approach to the golf swing based on anatomy,

research and physics rather than personal preference, bias or how the top

golfers in the world swing the club. It is designed to help anyone wanting to

learn how to become a great teacher develop a sound understanding of the true

core components of the swing. Because there is a lot of material to cover just

on how the body moves, there is little discussion on topics such as swing

plane, ball flight control, etc. These are reserved for Level 2 and Master RST

Certification. A strong base of knowledge is required before ever worrying

about those topics, and that strong base is provided both here in the Level 1

certification manual as well as the videos on the website at www.RotarySwing.com. Regarding the website videos, there are some

things that are much more easily explained in motion rather than print. Many

topics are omitted from this manual or only touched on lightly because they are

much more easily explained in the videos on the website. If you feel a topic

hasnt been covered enough detail here, it very likely has been online, so

check the website. It is updated each month with new videos and there is more

than 18 hours of content on there already.

If you are reading this

manual to become RST Level 1 Certified, you should be aware that the 130 plus

test questions on the exam are taken both from this manual and from the videos

on the website. Anything published under the RST section of the website is fair

game in the exam, and you should be fully prepared to answer questions from

both. At the time of this First Edition writing, a minimum passing score of 90%

is required to attain Level 1 certification. This is subject to change, but if

anything, the minimum passing score will move higher, not lower. We want to

ensure that the RST Certified Instructors are, quite literally, the most

knowledgeable, helpful and well-respected instructors in the industry and will

do whatever is necessary to protect that reputation. Your investment in RST

Certification will be one that will carry a high price tag for entry in terms

of study required but will bring with it the respect reserved for the brightest

experts in the golf world.

Good luck!

Given the complexity of the

movements of the golf swing and the precision required for success, it would

seem evident the need for a clearly defined and established set of fundamentals

from which to learn. Most everything else weve learned in life was based on

some industry-wide accepted set of fundamentals. When learning to play a

musical instrument, we never feared that if we took a lesson from someone other

than our normal instructor that he or she might teach us something completely

different or even opposite from our previous instructor. When learning to drive

a car, there were a common set of fundamentals. If you learned how to drive a

stick shift, you were taught to slowly ease out the clutch while gently

pressing in the accelerator. I doubt that anyone tried to teach you to slowly

let out the gas while gently pushing in the clutch! However, you can take ten different

golf lessons from ten different instructors and be taught ten different things.

How on earth could anyone learn this way?

Well, history has proven

they cant. Its a well known fact that golfers handicaps havent changed much

over the last 50 years, and I believe that instruction is at the root of this

trend. The most significant problem with golf instruction since its inception

is the fact that it has never been taught on a common set of fundamentals for

the simple reason that no one seems to be able to agree on any. This is to be

expected given how each instructor has come up with his own fundamentals that

he teaches. Most instruction material published in the past has been based on

how the top player of that era swings the golf club. Thats it. No underlying

explanation for why or how, just this works for me so you should do it to.

When Bobby Jones was the greatest golfer in the world, everyone wanted to learn

to swing like Jones. When Ben Hogan became the next world beater, he became the

most sought after swing guru and published a book that is still a favorite

amongst golfers today. But then a young kid named Jack Nicklaus came along and

swung the club and arms in a much more upright fashion with a massive leg

drive. All of a sudden, Hogans more flattish swing plane was no longer in

vogue. Today, of course, like lost puppy dogs trying to find someone to feed

them, countless instructors will put your swing up next to Tiger Woods and say

Heres what Tiger does, and heres what you do. Dont what Tiger does. They

do this all while having little to no understanding of the biomechanics of

Tigers swing, including the faulty movement and setup patterns that have

caused him injury. It wont be long before Tigers swing is overtaken by

someone else who hits it longer and straighter, and that golfers movements form

the basis for the next model swing.

If this seems insane to you--changing

the core of what golf instructors teach based on whos the top dog at the

moment--that's because it is. At some point, it just makes sense to ignore how

all the golfers on the PGA Tour swing and take a completely objective look at

human anatomy, physics and human physiology and say How is the body designed

to accomplish the task of striking the golf ball safely, powerfully and

efficiently, and how can the brain learn this new movement pattern? If that

makes sense to you, then the Rotary Swing Tour will make sense to you because

thats exactly what we did. Rather than define a set of fundamentals based on

our own biases or preferences of golfers swings that we liked or instructional

advice we felt made good tips, we decided to put together a set of

fundamentals based on the very definition of the word. According to Websters

Dictionary, a fundamental is:

a: serving

as an original or generating source

b : serving

as a basis supporting existence or determining essential structure or function

c: of central

importance

d: of or relating to essential structure,

function

When determining what a fundamental of the RST golf swing

is, it must first meet these criteria. To make things simple, below is a list

of synonyms and antonyms to memorize:

Synonyms of Fundamental

Primary

Origin

Central

Absolute

Antonyms of Fundamental

Secondary

Consequential

Peripheral

Dependent

So, from this point

forward, anything that is truly a fundamental of the golf swing should stand

the test of being primary, origin, central and absolute. If it does not, then

by its very definition, it cant be a fundamental.

Exercise

List 5 fundamentals of the

golf swing that meet the above criteria.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Its likely that youll find it difficult to do so, especially if someone

challenges you to defend your answers. For instance, lets take swing plane. To

many instructors swing plane is all the matters. They are unconcerned with how

the body moves, focusing only on the arms and hands and how they create a swing

plane. However, swing plane can NOT be a fundamental of the golf swing

according to the definition of the word because it is completely DEPENDENT on

the movements of the body, arms and hands. It is SECONDARY to these movements

and DEPENDENT on how the muscles in the body fire and happens in the PERIPHARY

of what is central to the golf swing the movements of the body. If youll

notice, swing plane fits perfectly with all the antonyms of what a fundamental

is. Were not saying swing plane is not important, but it cannot, by

definition, be a fundamental.

In your quest to understand

the truths about the golf swing, defining what a fundamental is and is not will

take you a very long way toward finding what truly is important in the golf

swing. If we revisit our swing plane example above, you will find that understanding

how to correctly rotate the torso, perform shoulder elevation and right elbow

flexion will create a swing plane. The club, by itself can do nothing, the

muscles of the body moving the bones at their respective joints are what create

the appearance of a swing plane, and therefore, each movement individually can

be looked at as a fundamental as they are the ORIGIN of movement.

For some, the swing plane

example may be too complex to understand at first, so lets take an easier one:

stance width. Think to yourself what you have been told regarding stance width

or perhaps what you have even taught your students. The most common advice is

that the feet should be shoulder width apart. When I hear this, the first thing

I do is ask that instructor, "Where are my legs attached, my shoulders or

my hips?" Of course, they answer the hips. So my next question is, "What

does the width of my shoulders have to do with the width of my stance?"

There is NO direct correlation between the two. Some golfers have very broad

shoulders and very narrow hips and vice versa. This useless piece of advice is

not only vague but not based on anything central or absolute. And worse yet,

the instructor cant provide an answer as to why he wants me to do it, and

that is unacceptable. Everything you do in the golf swing should have a very

clear answer as to WHY it needs to be done that way and HOW to go about doing

it. With RST, there is a very clear answer as to why, either based on anatomy,

swing mechanics, physics or the physiology of the learning process and a very

clear pathway on how to go about doing it.

For RST Instructors, the

width of the stance is a fundamental that abides by the laws of why and

how. First, it is determined by the width of the pelvis since that is what determines

neutral joint alignment (NJA), which is vital for power and injury prevention.

Second, it is determined by the fundamental in the swing of weight transfer, which

is inherent in all throwing and hitting athletic movements as it creates

momentum that is again, necessary for maximum power. Third, while transferring

the weight, we need the head to stay centered to make clean contact more

consistently. A clean strike becomes increasingly difficult with our heads

moving all over the place. Finally, it is based on the need to have the left

hip in neutral at impact for safe and efficient rotation. Because of these

requirements, the stance width for RST is 2 inches outside of neutral. This is

the type of analytical thought process that goes into understanding each piece

of the RST.

The point of this chapter

is for you to understand that you should question absolutely everything youve

heard about the golf swing in the past and everything you hear in the future.

Anytime someone gives you a piece of swing advice, see if it qualifies as a

fundamental and ask them the all important question, Why? Why is a very scary

question for many golf instructors because they dont have a clue why. They

were either taught to do it that way by another instructor, read about it in a

golf instruction book or found it to work in their own swing that is very

likely built around a chain of compensations. In all probability, they will

have no irrefutable answer for why they want someone to move the way they are

asking. If they cant answer why, then you should very seriously reconsider who

youre taking lessons with and how their lack of knowledge may be putting you

at serious risk for injury. If you, the instructor, want to have the answer to

why going forward, youve come to the right place.

Before we can begin to

dissect the golf swing, we must first understand, as teachers, how the brain

learns. The brain is not engineered to learn at 100 mph. For example the

first time you climbed into a car to learn how to drive, your instructor did

not tell you to hop on the open highway and Floor it! You first learned where

all the controls were, what the pedals did and all the other fundamentals of

how the automobile works. You would most likely step on the gas for the first

time in a parking lot or on a backcountry road. This safe environment with

minimal distractions would allow you to slowly get acclimatized to the vehicle

and to learn the fundamentals of its operation. You would learn how the gas works,

how the breaks work, then the steering wheel, then the gear selector and so on.

And, you would learn each of these one at a time. In other words, you would take

in small pieces of information that your brain could easily digest and then

move onto the next bit of information. Mastering operation of the car would be

ingrained by repetition through practice with constant and immediate correction.

If youve ever taught someone how to drive a car, you know just how

overwhelming this process can be to the student for the first time. But, by

guiding them slowly, piece by piece, they learn each fundamental as you guide

them through the process. In this manner you or the person you are teaching

systematically learned how to operate the vehicle.

As this information is

processed by the brain and you continue to repeat the necessary tasks to

operate the vehicle, you begin to feel more comfortable that you would be able

to competently operate the vehicle at higher rates of speed and in an

environment with more distractions. Were not quite ready for the 405 at rush

hour, but were systematically working up to it. In other words, the more

pieces of information you learn to perform without having to think about it, the

more you are able to take on greater responsibility and stack more information

on top of what you have previously learned. Eventually, you're able to perform

numerous functions in order to operate the vehicle safely without giving it

much thought, although clearly driving and talking on a cell phone are still

too many tasks for most to be done safely.

If we take a moment to

think about this logically, the golf swing should be learned in the same manner

as how we learned to drive. Much in the same way that we learned each

fundamental individually and then stacked another one on top of it, we will do

the same in building our golf swing. It makes no sense for us to worry about

the downswing if we cannot set up correctly to the golf ball. Once we observe

a breakdown in a step, we must remove a piece and go back to perfect the

previous step. Ben Hogan figured this process out many years ago and stated

his position very eloquently:

You simply cannot bypass the fundamentals in golf any more

than you can sit down at a piano without a lesson and rip off the score of My

Fair Lady. Learning the grip, stance, and posture clearly and well is, in a

way, like having to play the scales when learning piano. The best way to learn

golf is a great deal like learning to play the piano: you practice a few things

daily, you arrive at a solid foundation, and then you go on to practice a few

more advanced things daily, continually increasing your skill.

The point of Mr. Hogan's quote is simply this:

learning is a systematic process and can only be successfully achieved through proper

practice and repetition.

|

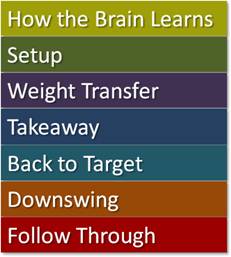

The Rotary Swing Tour Hierarchy of Learning |

The Rotary Swing model takes all of this into

account and is built around a hierarchy for learning the golf swing. It

contains the elements of a sound, biomechanically correct Rotary Golf Swing in

the sequence that they must be learned. Each segment of this hierarchy will be

covered in great detail in the following chapters.

Neuromuscular Re-education

Neuromuscular re-education

is the definition given to any form of athletic training, rehabilitation

program or bodily movement that requires muscles and nerves to relearn a

certain behavior or specific sequence of movements. It is important for us to

fully understand how our muscles and nerves eventually learn and develop the

neural networks and pathways necessary to perform a task effectively and

efficiently. As a new movement is introduced, the body begins to develop a

broad kinesthetic sense (sensation of muscle movements through nerves) necessary

to facilitate the movement (Dr. Larry van Such, https://www.athleticquickness.com/page.asp?page_id=53). As the first movement is perfected, the next

segment is stacked on top of that movement. This forces the muscles and

nerves to increase their kinesthetic ability or awareness to adapt to the new

movement. The process is repeated, and ultimately, the muscles and nerves

become perfectly coordinated together producing the desired effect. Every day

one practices, the brain is constantly refining the pathways necessary to

master these movements. This makes the movements appear effortless and without

any conscious thought. When one masters a new motor skill, the athletic

movement transitions from active effort to automatic ability. Essentially, the

new movement pattern becomes hardwired into the brain. This is known as

implicit or procedural memory.

It seems that as a motor

skill enters the implicit memory, the neural pathways responsible for

performing the task shift from one region in the brain to another. For

example, in one experiment magnetic pulses were used to trigger neurons firing

in the motor cortex in order to study neuronal activity during skill learning.

During the practice time, while the subjects were learning the skill, the

regions of neurons recruited got bigger, and the intensity of firing

increased. Once the skill was mastered, the region shrank to original size

again. Apparently a different region of the brain, probably the basal ganglia

or cerebellum took over once the task became automatic (https://www.brainskills.co.uk/LearningMotorSkills.html). Let us examine this in greater detail to further

understand this process. Scanning studies show that a person uses the frontal

lobe, motor cortex and cerebellum while learning a new physical skill.

Learning a motor skill involves following a set of procedures and can be

eventually carried out largely without conscious attention. In fact, too much

conscious attention directed to a motor skill while performing it can diminish

the quality of its execution. When first learning the skill, attention and

awareness are obviously required. The frontal lobe is engaged because working

memory is needed, and the motor cortex of the cerebrum interacts with the

cerebellum to control muscle movement. As practice continues, the activated

areas of the motor cortex become larger as nearby neurons are recruited into

the new skill network. However, the memory of the skill is not established

until after practice stops. It takes about four to twelve hours for this

consolidation to take place in the cerebellum, and most of it occurs during

deep sleep. Once the skill is mastered, brain activity shifts to the cerebellum,

which organizes and coordinates the movements and the timing to perform the

task. Procedural memory is the mechanism, and the brain no longer needs to use

its higher-order processes as the performance of the skill becomes automatic.

Continued practice of the skill changes the brain structurally. These skills

become so much part of the individual that they are difficult to change later

in life (David A. Sousa, http://www.sagepub.com/upm-data/12749_Sousa_Chapter_1.pdf)

An effective example of

this process is the movie The Karate Kid. In the movie, the teacher

asked the student to perform numerous repetitions of a particular movement, all

the while using very simple keywords that he kept repeating aloud while the

motion was performed. After a days worth of repetitions and hearing the key

words for one particular movement, a new movement was introduced the following

day with a new set of keywords. This continued for several days. On the final

day, the teacher engages the student in sparring and simply shouts out the key

words of the particular motion he wants the student to perform. Without even

thinking about blocking a punch or kick, the student simply performed the movement

associated with the key word being commanded. He proceeded to block every punch

and kick effectively without any conscious thought. While this whole process

may seem like Hollywood fiction, it is actually a perfect illustration of how

the brain learns most effectively and efficiently. This is the key point we

must take away from this example. Through research and data gathered while

working with stroke victims, we now know it takes the brain approximately 3000

to 5000 repetitions in order for the victims to master new motor movement

patterns. This is not something that ANYONE can short cut and still expect to

master a task. Three to five thousand is the average range of repetitions it

takes anyone to MASTER a new movement and put it into "auto pilot"

mode. That doesn't mean the student can't feel it, repeat it and understand it

intellectually after just a few reps, but they will not be able to come back

the following week and perform the task without having to give it conscious

thought. This is, in fact, one of the ways we test our students to ensure they

are ready to stack the next learning block. We ask them to perform the movement

they are working on while telling us what they had for breakfast. If they can

perform the movement flawlessly without skipping a beat in the conversation, we

know the brain has built a strong enough neural pathway that the student can be

challenged with the next movement.

Three to five thousand reps

sounds very daunting for most at first, but it is simply a fact of medical

science and there is no way around it. However, the student should take heart

in the fact that it only takes around 100 repetitions for the brain to actually

create a new neural pathway. The century mark should be the goal in your

lessons. If you can have your student perform 100 correct repetitions of the

movement in a one hour lesson, you have firmly planted the seed for change and

helped your student to truly make a lasting change in their golf swing. One

hundred reps in an hour is a LOT of repetition, and you will have to be

diligent to get it in. As you can imagine, there's not a lot of time for

hitting many balls in a truly productive lesson, but ask your student whether

they genuinely want to build a better golf swing or whether they want to keep

hitting balls the way they are now, struggling from one day to the next. Once

the pathway is built with that foundation of 100 reps, the brain will begin to

"insulate" those neurons in the pathway with a fatty substance called

myelin with continued repetition. This myelination acts as insulation that allows

the neurons to fire faster and is a critical biological response to learning. The

thicker this pathway becomes by being wrapped in more and more myelin, the more

automatic the task becomes for the student. However, this process is a rather

slow one and varies from one person to the next. The process of

"myelinization" takes anywhere from a few days to a couple of weeks, providing

further proof that giving a student a swing "tip" is a useless piece

of advice over the long term. Learning the golf swing is a neurological process

that requires physiological change in the brain and because of the biological

processes involved, REQUIRES TIME! To further help you and your students

understand the learning process, I highly recommend reading The Talent Code

by Daniel Coyle. It is a great book that details the learning process and will

serve as an invaluable reference to understanding how to truly help your

students improve.

Our hierarchy of learning

for the golf swing has been set up in the particular sequence you saw earlier for

a purpose and the drills and learning program are built around how the brain

learns as you have just read. The first building block of the hierarchy is

perfecting the setup. Once the setup has been mastered, the next step is

stacking the weight transfer. If at any time there is a breakdown in one of

the fundamentals of the setup, we must remove any instruction about the weight

transfer and readdress the setup. This follows the process of neuromuscular re-education.

This process should be continued throughout the course of building the student's

golf swing. We may find ourselves addressing the downswing when there begins

to be a breakdown in the takeaway. When this occurs, we remove each of the

subsequent pieces and go back to readdress the proper movements necessary to perform

the proper takeaway. This is due to the fact that so much of what occurs in

the golf swing is cause and effect based. While this process may not

necessarily be viewed as desirable by the student, it is necessary to impart

real change in motor patterns rather than allow the student to expect to make

any lasting change in his or her golf swing with a quick fix. There are no

quick fixes in the golf swing, only temporary ones.

It is imperative that you,

as the instructor, not only clearly understand the way the brain learns but

also clearly convey the process to the student. When the student fully

comprehends that there is only one path to true, lasting change and

improvement, they will have no choice but to embark on the journey with you and

be more committed to the process. More importantly, understanding the

underlying biological processes involved in learning will help them understand

why they failed to improve in the past and give them further hope that they can

improve going forward by following your guidance.

Review questions:

1. How many repetitions

does it take for a person to master a new motor movement and why?

2. What is myelin and what

role does it play in the learning process?

3. How many repetitions

does it take for a new neural pathway to be created?

4. List the seven steps to

the Rotary Swing Hierarchy of Learning.

The concept of Push vs.

Pull is central to the Rotary Swing Tour. Sir Isaac Newton determined that all

movement is either a push or a pull. You can envision this very simply by

thinking back to the days where golfers actually walked the course with the

assistance of pull carts. If you ever used one of these, you noticed right away

that it was much easier to keep the pull cart moving in a straight line when

you let it trail behind you and you pulled it. When you tried to push it from

behind, you would invariably develop a little zig-zag path as the movement

seemed less stable. But why?

When we look at the

definition of a pulling motion in its simplest form, it is the act of moving

something towards you; or towards center. A push is the exact opposite. If you

are trying to push a box across the floor of your living room, are you

effectively moving it away from you or toward you? The reason that the pull

cart travels in a much straighter line when pulled is that the force acting

upon it is always moving it toward a centralized point YOU! When you stand

behind it and push it, it could move in any number of directions, a full 360

degrees away from center. When we apply these concepts to the golf swing, some

very interesting things begin to appear that make a lot of the old instruction

adages like get your left shoulder under your chin obsolete. We would, in

fact, tell the student to pull his right shoulder behind his head.

First off, lets define one

of our goals in the golf swing that is a fundamental of the RST. That is the

goal to create centered rotation around the spine. The spine serves as a

perfect axis around which to rotate in the golf swing if you want to stay

centered and not shift laterally off the ball. If that is our goal, then the

next logical step is to look at the motion that would allow us to accomplish

creating centered rotation.

In our pull cart example,

we were only talking about pushing and pulling as it pertains to linear motion;

ie. You walking down the fairway toward your next shot pulling the pull cart

behind you. But the golf swing by nature is rotational, so we need to introduce

two more concepts from Mr. Newton centripetal and centrifugal force. By

definition, centripetal force is: the force that is necessary to keep an

object moving in a curved path and that is directed inward toward the center of

rotation (Websters Dictionary). The definition for centrifugal force is: the

apparent force that is felt by an object moving in a curved path that acts

outwardly away from the center of rotation (Websters Dictionary).

Technically speaking, centrifugal force is a false force that is simply a

result of centripetal force. The reality is centrifugal force doesnt exist at

all, and no object would continue rotating around a centralized point without

the aid of centripetal force or gravitational pull. Rather, it would continue

on in a straight line. However, centripetal force is very real, very powerful

and amazingly efficient.

To fully understand

centripetal force, imagine a ball on the end of a string attached to a stick.

By moving the stick in a very small circular motion, the ball on the end of the

string can be accelerated to terrific speeds with minimal effort by you. Your

tiny hand movements are creating centripetal force and are always pulling in

the opposite direction of the ball to keep it moving at the highest velocities.

The bigger you make your hand movements, the slower the ball begins to move and

the more effort you have to put into moving the stick to continue accelerating

the ball. As part of these bigger movements, it also begins to become much more

difficult to keep the ball orbiting on a constant plane. Upon reaching maximum

speed, the string will naturally extend to 90 degrees in relation to the stick

and the ball will travel on a single plane around the stick as long as the

stick remains centered and moving with the same simple, tight little movements.

The looser the movements, the more difficult it becomes to keep the ball on

plane.

Figure 2 - A simple illustration of the concept of the ball on the end of a string.

Its not hard to see how

this analogy directly relates to the golf swing as the concepts of plane and

rotation are thrown about all the time in the instruction world. The key in the

Rotary Swing Tour is that the plane is very easy to control when we understand

how to create centered rotation when using the concepts of push/pull and

centripetal and centrifugal force.

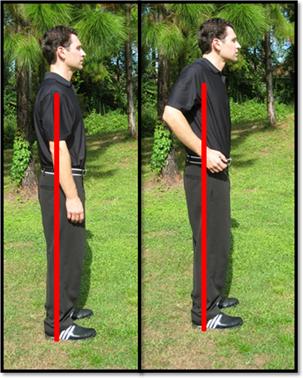

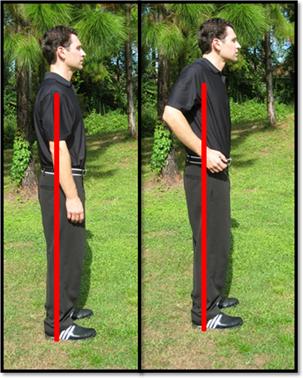

Figure 3 - Note how the head does not want to remain centered when pushed.

Lets first take pushing

and pulling into a real world example as it applies to the golf swing. To do

this, youll need a partner. Stand upright and hold a club horizontally tight

across your chest. From behind, have someone move you by pushing you from both

sides of the club. You will notice if you look in a mirror, that your head will

move about in both directions and you will likely not make a 90 degree turn.

Now, have your partner pull the end of the club back behind you. You will be

amazed at how easily you can make a full shoulder turn and how much tighter

and smaller the movements feel when compared to pushing. Take a look at the

images to see this more clearly.

In the first image, when

pushed from either side the head moves away from center, as does the rest of

the body. For most golfers, this is exactly how they try and take the club back

during the backswing. They simply push the left arm across the body by pushing

from the left side and then wonder why they cant make a full shoulder turn. If

you want to turn your back to the target, then, quite simply, turn your back.

Lets look at what it looks when you are pulled from behind instead.

Figure 4 - This is what efficient rotation looks like when created by a pulling motion.

When being pulled, your head stays centered and the

body can easily make a full shoulder turn without moving off the ball. Youll

notice in the pull images that the head remains very centered. More

importantly, you can feel this when your partner pulls you. This is the key to

golfers of all flexibilities making a full shoulder turn and is the key to

creating centered rotation around the spine. To date, Ive yet to have a single

golfer Ive ever taught not be able to make a full 90 degree turn, no matter

their age, fitness level or flexibility so the next time your student tells you

hes not flexible enough to make a full shoulder turn, pull out this simple

drill and watch his eyes light up.

Once weve figured out why

we want to pull and the benefits of doing so, the final goal is to look at

exactly HOW we create this rotation. This is where a basic understanding of

anatomy comes in handy for the instructor. Obviously, when doing the push/pull

exercise earlier, you had someone creating the force for you by pulling or

pushing on the golf shaft. Now, your muscles need to create that same force,

but which ones? Fortunately, for creating rotation of the torso, there are

relatively few muscles that you or your students need to be aware of. The first

set of muscles that facilitate rotating the torso are the obliques. If you have

your student sit at the edge of a chair and begin turning his torso from side

to side with some speed, he will quickly become aware of his obliques. Well

talk more in detail about these muscles later. The second set of muscles the

golfer will become aware of are a group of muscles in the back. Specifically,

we refer to the lower trapezius and latissimus muscles. The lower trapezius

muscle and rhomboid work to pull the scapula toward the spine (center) during

the backswing and when done correctly, the golfer will feel the latissimus

muscle activate. We generally dont refer to the rhomboid because most golfers

havent a clue what it is, nor can they feel it. Which is the exact reason we

refer to the lat quite frequently. While it is the lower trapezius, not the

latissimus, that is moving the scapula, most golfers cant feel it, but they

can feel the lat. Well discuss this more in depth later as well.

Using the scapular motion

of gliding it across the ribcage in toward center helps create centered rotation

exactly like what we are looking for and gets the golfer connected to the big

muscles of his core. Its a win-win for the backswing. This movement is a key

component for the golfer learning to create a pulling motion, which, as we

have learned, is necessary for creating an efficient, centered rotation and

will be a key to helping all your students create a 90 degree or greater

shoulder turn in the backswing. While we have gone to great lengths in this

chapter to emphasize the pulling motion desired to create centered rotation, it

should be noted that this is not the only force that is going on. In fact,

technically speaking, it is a "push-pull" throughout the golf swing.

As an example, we emphasize pulling with the left oblique on the downswing

because this is what helps clear the hips back out of the way, providing room

for the arms on the downswing. Most golfers push from the right side during

the downswing and end up coming out of their spine angle. This is more

instinctual for most but creates a number of common swing faults. When the

golfer begins to focus his efforts on pulling, it is often a new feeling for

him, so that's all he "feels." However, while he may feel the left

oblique firing, the right oblique is also helping as they work in pairs in

rotating the torso. It is important for the student to feel pulling over

anything else in most cases, but as an expert golf instructor, you need to

understand that both sides are working.

Review questions:

1. According to Newton, all

movement is a push or a pull. In what direction does a push move and which

direction does a pull move?

2. If the golfer wishes to

remain centered, should he or she push or pull during the swing?

3. Explain centripetal and

centrifugal force as it relates to the golf swing.

Figure 5 - These are the primary muscles you should fully understand their functions during the golf swing.

One of the primary keys to power in the golf

swing is in the application of the large core muscles. The term, in the box

is a central concept around which the Rotary Swing Tour model is based and

refers to these large muscles in the torso. In this chapter, you will want to

come to fully understand the term in the box and its opposite, in the

rectangle, as these are the simple terms we use to convey connection to the

large and highly interconnected core muscles. Before we can come to an

understanding of exactly what these terms mean, we must first review some basic

anatomy. It is necessary to clearly define several of the major muscles of the

body and their functions for the golf instructor to successfully teach a

student how to move and where to move from in the golf swing. The goal is for

the Rotary Swing Instructor (RSI) to fully understand how using the muscles in

the rectangle is detrimental to achieving the goal of an efficient, repeatable

golf swing. Conversely, the RSI needs to have a firm grasp of why staying in

the box is essential for power and control.

The rectangle can basically

be defined as the muscles of the neck and upper torso such as the trapezius and

the muscles in the shoulders located both anteriorly and posteriorly. More

specifically, it includes the following muscles and their corresponding

functions:

Deltoids (Delts): raises arm

away from body to front, side, and rear

Upper Pectoralis Major (Pecs):

draws arm toward body and rotates upper arm inward

Trapezius (upper fibers) (Traps):

elevate the scapula causing a shrugging motion of the shoulders

The box can be defined as the muscles of the core of

the body, both anteriorly and posteriorly. It includes the following muscles:

Rectus Abdominis (Abs): flexes spine and draws pelvis forward

Internal Oblique Abdominal (Obliques): flexes and rotates the trunk

External Oblique Abdominal (Obliques): flexes and rotates the trunk

Trapezius (middle fibers) (Traps): retract the scapula, drawing it towards the body's

midline

Trapezius (lower fibers) (Traps): depress the scapula, drawing it inferiorly

Latissimus Dorsi (Lats): largest surface area of any muscle in the body; rotates

and lowers arm, pulls shoulder blade back

Because it takes approximately 32 pounds of muscle

to swing the golf club at 100 mph (The Physics of Golf, Ted Jorgensen),

it is vital that we tap into the larger muscles of the core. The musculature

of the upper back, neck, and arms is simply not large enough in most golfers to

generate the necessary horsepower, nor is it designed to create rotation around

the spine. Golfers who swing from the rectangle often appear to be making a steep

chopping motion at the ball rather than an efficient rotary motion. This

chopping motion is very inefficient, both from a swing mechanics and

biomechanics perspective. When we engage the muscles in the rectangle, we anatomically

lose our link to the large muscles in the box. As youll learn, the scapula

is the central component to maintaining the connection to the large muscle

groups. It is imperative that the proper position of the scapula be maintained

during the swing for the golfer to remain in the box to generate power from the

large core muscles. The following is from the Journal of the American Academy

of Orthopedic Surgeons:

This scapula is pivotal in transferring forces and

high energy from the legs, back, and trunk to the delivery point, the arm and

hand, thereby allowing more force to be generated in activities such as

throwing than can be done by the arm musculature alone. This scapula, serving

as a link, also stabilizes the arm to more effectively absorb loads that may be

generated through the long lever of the extended or elevated arm.

W. Ben Kibler, MD and John McMullen, ATC

Journal

of the America Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, Vol 11, No 2, March/ April 2003

Figure 6 - What muscles do you feel engage when shrugging your shoulders up vs. having them depressed?

In short, allowing our shoulders to shrug,

thereby getting into the rectangle, typically results in a weak, armsy slap at

the golf ball as the golfer anatomically loses the link to the large muscles of

the back. It is imperative for the student to learn how to get into the box

and remain there for the duration of the swing into impact.

Students can get the feeling of getting into

the box by depressing their shoulders and retracting them slightly. This brings

us to our first set of cue words, Shrug/Depress. When students shrug their

shoulders, they should immediately feel all the muscles in their upper

shoulders and neck area engage. If they pull their shoulders forward and up,

they may notice the pectoralis major engage as well. When students depress

their shoulders and retract them slightly, they will feel their Latissimus

(lats) muscles engage -- think good posture or military posture. When they

feel these muscles engage, they are, effectively, in the box. The shoulders and

chest should be relaxed and feel very open. The abdominals should now be

engaged by the student to add stability and remove any excess lordosis (forward

curvature; swayback) in the spine. Have them pull their belly button in toward

their spine to properly support the lower back. They have now established a

connection to the larger muscles in the core of the body. If, at any given

time during the course of the swing, the shoulders are allowed to shrug and get

out of the box and into the rectangle, the link to the core is broken, and it is

difficult to regain during the downswing. If the student doesnt reconnect at

some point, he is now forced to swing the golf club with the shoulder and arm

musculature alone, with minimal assistance from the larger core muscles.

Few golfers can reconnect during the transition or

downswing, and it is simply an inefficient and extra move to do so. Lorena

Ochoa is a good example of a golfer who disconnects going back but then

reconnects coming back through. Jim Furyk is another example. You can easily

see the inefficiencies in these two golfers swings and imagine how difficult

it would be to teach the typical amateur these moves. Therefore, it is

paramount that the student remains in the box throughout the swing, to build

the simplest and most powerful swing possible.

Review questions:

1. Define the terms

"Box" and "Rectangle.

2. Why is it important for

the golfer to remain "In the Box" during the swing.

3. Are there muscles in the

"Rectangle" designed to create rotation around the spine?

4. What are the primary

muscles in the "Box" that create rotation?

Figure 7 - Note the "rounded" appearance of the shoulders when the palms face the front of the thighs.

The grip is another fundamental of the golf swing

that has been taught numerous different ways over the years. From Hogans weak

grip to Ernies strong grip, each has had his preference. When we look at the

grip from an outside perspective, there are two requirements that we must first

consider. The first is neutral joint alignment, and the second is what factors

allow the clubface to be squared at impact most efficiently while still

allowing a free release of the club.

When referring to NJA, the most common myth

regarding the grip is that you should grip the club based on how your hands

naturally hang at address. For instance, when you take your setup position

without a club, if your arms naturally face the front of your thighs at

address, you should grip the club with a stronger grip, and if they face the

sides of your thighs, you should have a more neutral grip. Of course, this is

ridiculous advice; not to mention potentially harmful causing undue stress to

the shoulders and right elbow. No ones arms naturally hang and face the front

of their thighs, this is simply a by-product of bad posture. This happens when

the golfer allows the shoulder blades to protract, which creates a slumped or

rounded appearance of the thoracic spine (the mid to upper back area). From

this position, the golfer must rotate his arm 90 degrees or more to grip the

club; not to mention the issues it creates with the swing itself. With the

shoulder blades retracted and in neutral, the palms naturally face each other

and make it very easy to take a grip that meets the requirements mentioned

earlier.

In this neutral position,

the Vs in the thumbs point vertically, straight back up the arms. Yet, as the

left arm reaches slightly across the body to grip the club, a slight clockwise

rotation of the arm occurs and the shoulder blade protracts slightly. The

larger chested the person, or the bigger arms they have, the more this

protraction and rotation will have to occur to grip the club without bending

the left arm. This movement turns the V to a slightly stronger position where

it is pointing to the right side of the head. As you move to position the hand

with the pad of the palm over the handle, which is necessary for increased

leverage, this further moves the left hand into a stronger position. As the

last three fingers of the left hand cinch up to secure the club and the thumb

and forefinger are pinched together, the shape of the V will fully take place

and the final grip will be in a slightly stronger than neutral position. This

allows the clubface to square more easily with minimal manipulation of the

hands through the hitting area, all while protecting the joints from undue

stress.

In this neutral position,

the Vs in the thumbs point vertically, straight back up the arms. Yet, as the

left arm reaches slightly across the body to grip the club, a slight clockwise

rotation of the arm occurs and the shoulder blade protracts slightly. The

larger chested the person, or the bigger arms they have, the more this

protraction and rotation will have to occur to grip the club without bending

the left arm. This movement turns the V to a slightly stronger position where

it is pointing to the right side of the head. As you move to position the hand

with the pad of the palm over the handle, which is necessary for increased

leverage, this further moves the left hand into a stronger position. As the

last three fingers of the left hand cinch up to secure the club and the thumb

and forefinger are pinched together, the shape of the V will fully take place

and the final grip will be in a slightly stronger than neutral position. This

allows the clubface to square more easily with minimal manipulation of the

hands through the hitting area, all while protecting the joints from undue

stress.

The right hand also has to

work across to the center of the body where the club will be at address, but

does so a little differently. In order to avoid significant scapular protraction

created by reaching across the body to take the grip, the golfer employs axis

tilt by bumping the hips slightly toward the target while keeping the head

stationary. This tilts the spine away from the target while moving the right

arm closer to the club so that it can take its position. While there is some

protraction of the scapula, it should be minimized. The right arm will work

across the body maintaining NJA with minimal rotation in a more under handed

motion, placing the right hand in a position where the V points to almost

directly up the right arm toward the right shoulder, which would be parallel to

the V on the left hand. Because they are parallel, they cannot both point to

the same spot, the V on the left hand will point to a spot slightly closer to

the head of the golfer while the V on the right will point to a spot further

from the head, toward the shoulder. This puts both hands in a balanced position

that is neutral so they can work together to square the club.

Figure 8 - Note the direction of the "Vs" when the arms are in NJA.

Figure 8.1 - The "V" formed by the left thumb will point toward the right side of the body in between the head and shoulder.

Figure 9 - Note the green line leans away from the target

as the right hand is brought to the club correctly rather than protracting the

shoulder blade and reaching across the body.

Figure 10 - As the right hand is brought onto the club, the wrist remains in neutral, causing the "V" to point directly back up the right arm toward the right shoulder.

Grip Pressure

We are very fortunate to

work with Dr. Jeff Broker, who is on the Rotary Swing Advisory Board and is a

leading researcher in the field of grip pressure. His research of golfers

primarily at the lower handicap level has revealed one thing conclusively and

that is that grip pressure is NOT constant throughout the swing. Unequivocally,

grip pressure changes throughout the swing, starting from very light to

significantly higher at impact.

Starting with a baseline

for each golfer's maximum grip pressure (MGP) being benchmarked at 100%, the

average pressure at address is in the range of 20% MGP. At the top of the swing

during the change of club head direction, the grip pressure increases and then

peaks to around 80% MGP at impact. In other words, good golfers are holding on

nearly as hard as they can through impact. This should seem obvious due to the

fact that the club effectively weighs as much as 100 pounds due to centrifugal

force. However, the golfers do not realize they are gripping the club this

tightly through impact. They feel as if it is constant, and thats a good

feeling for the golfer to focus on because tension at the wrong times will

inhibit the proper movements and decrease speed. Just like all things in the

golf swing, the proper timing makes all the difference.

That being said, there are

a couple of key points that need to be made regarding pressure points in the

grip. The first has to do with the last three fingers of the left hand. Because

of where the muscles that move them attach in the left forearm and both the

pulling action of the left arm in the downswing and the uncocking (ulnar

deviation) of the left wrist in the downswing, it is imperative that these

three fingers securely grasp the club. The left hands primary job coming into

impact is to control both clubface direction and loft while uncocking the left

wrist. The uncocking places the left wrist in a secure position, limiting unnecessary

unhinging. This is particularly important to learn early on for beginning golfers

as the most common swing fault at impact is this unhinging of the left hand,

commonly referred to as flipping or cupping. With the left wrist fully

uncocked, flipping the club becomes very difficult, and the stability provided

by this motion will help significantly with clubface control.

Figure 11 - The wrist positions that need to be understood in the golf swing.

While the right hand

assists with controlling loft and, to a lesser degree, clubface angle, its role

is no less important. The right hand is primarily responsible for transmitting

speed from the trunk to the club head and, obviously, it can only do so through

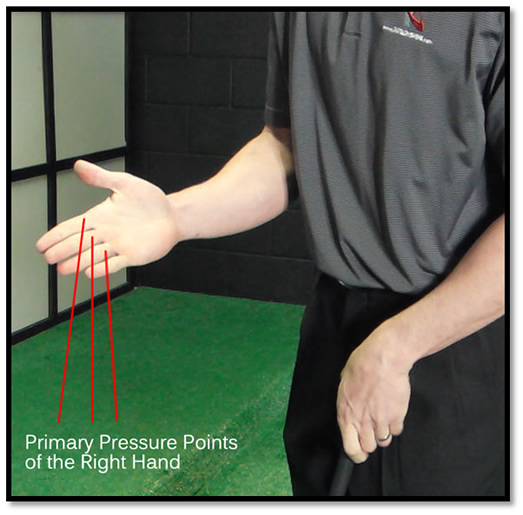

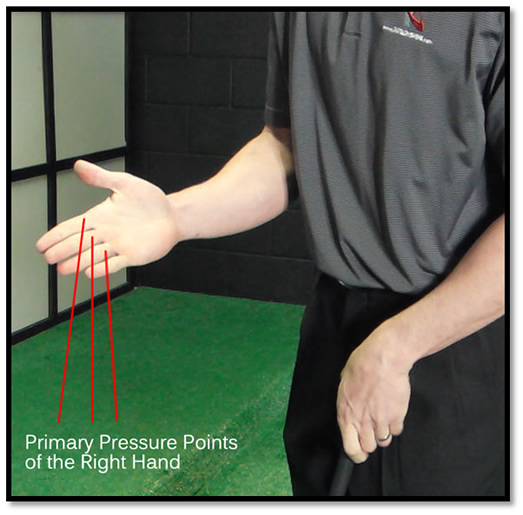

its contact points on the club, making them of supreme importance. There are three

primary pressure points on the right hand that the golfer must become aware of

to accelerate through and control impact. They are the proximal phalanx (the

bone at the base of the finger) of the index and middle two fingers. These key points will be responsible

for transmitting forces created by the rotation of the trunk, the right pec and

the extension of the right tricep, to name just a few. If the golfer is not

aware of these points and doesnt learn to monitor them, he can struggle with

both a lack of clubhead speed and a lack of clubhead control. They are also

vital for having a sense of control of the golf club during the backswing and will be one of the key focus points in

the Right Arm drills used later in this book.

While the right hand

assists with controlling loft and, to a lesser degree, clubface angle, its role

is no less important. The right hand is primarily responsible for transmitting

speed from the trunk to the club head and, obviously, it can only do so through

its contact points on the club, making them of supreme importance. There are three

primary pressure points on the right hand that the golfer must become aware of

to accelerate through and control impact. They are the proximal phalanx (the

bone at the base of the finger) of the index and middle two fingers. These key points will be responsible

for transmitting forces created by the rotation of the trunk, the right pec and

the extension of the right tricep, to name just a few. If the golfer is not

aware of these points and doesnt learn to monitor them, he can struggle with

both a lack of clubhead speed and a lack of clubhead control. They are also

vital for having a sense of control of the golf club during the backswing and will be one of the key focus points in

the Right Arm drills used later in this book.

Figure 12 - These three points are crucial for directing force in the downswing and sensing the clubface and lag.

To provide a little more

feel, dexterity and sensitivity for the index finger, there is often a gap

between it and the middle finger. This positions the club slightly more toward

the knuckle, or proximal interphalageal. In working with your students, youll

simply focus on the pad of flesh near the base of each finger.

To provide a little more

feel, dexterity and sensitivity for the index finger, there is often a gap

between it and the middle finger. This positions the club slightly more toward

the knuckle, or proximal interphalageal. In working with your students, youll

simply focus on the pad of flesh near the base of each finger.

Once these fingers are

positioned correctly, the last necessary piece is to secure the thumb to the

side of the palm where the Vs are formed. This is imperative for the right

hand. You will be able to detect golfers who are primarily just swinging with

the left arm and not applying force from the right side simply by observing

this position at address before they ever move the club. Golfers who dont use

the right hand to transmit force will tend to have a space between the thumb

and hand, making it more difficult to sense the club in the right index finger

and requiring that they over use the left hand at the top of the swing to

prevent the club from falling down in between the space between the thumb and

right hand. Securing the thumb and hand together allows the right hand to

properly support the club at the top of the swing while helping secure the

right index finger in place on the grip.

Figure 13 - Note how the club runs through the fingers on the right hand. For speed in the downswing, it is critical that the club not rest high in the palm. Think of the way the club sits in the right hand similar to how a fishing rod would rest in the hand while making a long cast.

Review Questions

1. Should the thumb and side of the hand have a space between them or

be pinched together?

2. Where should the Vs of each hand point?

3. Describe the key pressure points in each hand.

The setup is the one

fundamental in the golf swing which every golfer can execute correctly every

time. The goal for our setup is to ensure that our bodies are anchored to the

ground in such a way that will provide a stable, centered platform for the

rotation of the upper torso and that the proper muscles are engaged for correct

posture, stability, and power. Our goal for this chapter is to become educated

in the proper means of getting our students set up correctly every time. We

also need to be aware of the most common setup flaws and their impact on the

rest of the golf swing.

Critical Thinking: List 4 common

fundamentals of setup taught in the golf industry today

1.

1.

2.

2.

3.

3.

4.

4.

Let us first discuss proper

setup position which should include all of the following elements:

Stance width: 2 inches outside

of neutral joint alignment

Weight centered over the center

of the ankle joints (or slightly forward of that)

Spine in neutral joint alignment

Shoulders blades feel retracted (in

neutral)

Lower abdominal muscles engaged

to remove excessive curvature of lumbar spine

Arms: hanging naturally under the shoulders and the hands

under the chin

Elbows: Pits facing directly forward toward the target

line (left pit will be rotated slightly away from the target with a grip that

is stronger than neutral)

Ball position: directly off the left ear

Axis Tilt: 2-10 degrees of tilt depending on build, shot

and club

Figure 14 - From down the line, a view of the joints in neutral. Note that the red line marking the “tush line” is considerably behind the heels when viewed from this angle. This clearly indicates the weight is back over the ankles rather than being over the balls of the feet. From this position, it is easy for the golfer to feel the powerful glute muscles engage right from the setup for stability in the swing.

Stance

width: 2 inches outside of neutral joint alignment

Stance

width: 2 inches outside of neutral joint alignment

Before we can further

discuss stance width, we must first understand the definition of Neutral Joint

Alignment (NJA). This term refers to when the joints of the body are in

neutral, such as when, from a lateral view perspective, a straight line can be

drawn from the center of the ear hole down through the center of the shoulder

and hip joints, the back of the knee joint and through the center of the ankle

joint. In the image to the left, you can see NJA from the side in regards to

the center of the ankle lining up with the back of the knee which lines up with

the center of the hip, which in turn, lines up with the center of the shoulder.

In addition, when observing

the anterior view, NJA when referring to the lower body can be defined by a straight

line running directly through the center of the hip joint, the knee and the

center of the ankle. We wish the student to set up with the center of each

ankle approximately 2 inches outside of this neutral joint alignment position.

This is not an arbitrary measurement. This is the widest the stance can be in

order to prevent lateral head movement from occurring throughout the golf swing

while still allowing for a proper weight transfer. In other words, this

position will allow us to provide a wide, stable base without forcing the upper

body to shift laterally to transfer weight. It is important to understand

lateral head movement will dramatically affect the balance of the golfer and

the ability to consistently strike the ball cleanly. If the head is forced to

move laterally in the backswing, the natural bottom of the swing arc moves with

it. An excessive lateral shift must now be employed in the downswing, which

will create movement linearly towards the target. The resulting downswing will

can lead to a loss of speed and make it harder to keep the bottom of the swing

arc consistent. Some head movement is normal, but RST strives to minimize it in

order to preserve the swing center. As discussed in an earlier chapter, stance

width is determined by the width of your pelvis, which can be easily

established by locating the boney hip bones that tend to protrude on the

front and side of the lower abdomen. On average, these bones sit about "2

finger widths" outside the center of the hip socket. The width of two

fingers is close enough to establish neutral joint alignment and achieve the

proper stance width.

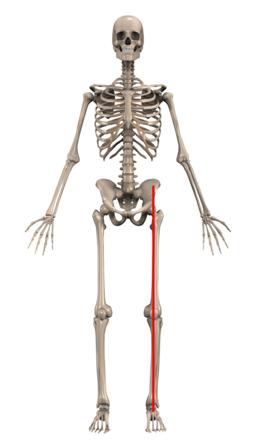

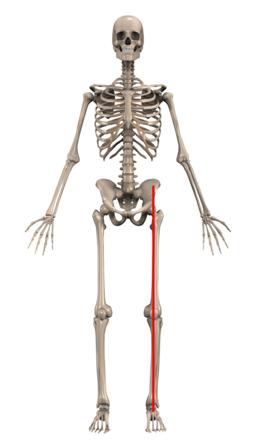

The image of the skeleton on

the next page shows NJA of the hip, knee and ankle. Note that the red line runs

directly through the center of these joints. From this position, the golfer

should go approximately 2" wider on either side for the proper stance

width.

Figure 15 - When viewed from face on, a straight line drawn from the center of the hip socket will go

straight through the center of the knee and the center of the ankle.

Weight centered over the center of the ankle joints

If we refer once again to

the lateral view anatomical diagram provided earlier, we can plainly see the

line runs from the back of the knee joint directly through the center of the

ankle joint. This is the way our body was designed to bear weight in order to

be balanced and support the weight of the rest of our body. We want to

accomplish much of the same when setting up to a golf ball.

Traditional instruction

repeats to us over and over again that the weight should be on the balls of our

feet. This is not the way the body is intended to bear its weight and remain

balanced. In order to remain centered and balanced and fight the significant

centrifugal forces occurring through impact, we must prepare ourselves to

utilize our bodies anatomical design. Having the weight centered over the

ankles at address not only moves our weight back such that we can fight the

inertia of the club during the downswing but also allows the two

"chunkiest" muscles in the body to be fully engaged to provide stability

for the rotating torso. The gluteus muscles will be engaged more effectively

when the weight is back over the ankles, providing a tremendous amount of

stability and power for the golf swing. As the golfer moves his weight toward

the balls of the feet, the gluteus muscles begin to transfer the load to the

quadriceps, or the front of the thighs. The primary role of these muscles is to

move the lower leg away from the body (imagine kicking a soccer ball). They are

not designed to support the hips for the rotation that is required during the

downswing; however, the gluteus muscles serve this role perfectly. We establish

the golfer in a truly balanced position with his weight on his ankles for this

reason as well as the fact that it is necessary for rotation in the downswing,

which we'll cover in more detail later.

Let us briefly discuss how

we can get the student into this position with the weight centered over his ankle

joints at address. The procedure for the correct setup should be as follows:

Stand straight, in the box,

and firm the knees

hinge from the hip, keeping the

spine neutral, which will cause the backside to protrude behind

the student should feel the

weight shift back into their heels to the point that their toes begin to raise

up off of the ground

once the weight is all the way

back into the heels, relax the knee slightly and the student should feel the

weight now centered over the ankle joints

bump the left hip slightly

toward the target while keeping the head stationary, creating axis tilt

have the students roll the

ankles in slightly

Figure 16 - Note the sequence. Good posture is established first, then the hips hinge, keeping the spine intact, then the knees are relaxed slightly.

Now that we have systematically discussed the How of the setup, let us take a

moment and examine the What of each step in the process. We have the

student stand straight and lock the knees because it is very easy to introduce

excessive knee flex when first setting up to the golf ball. Excessive knee

flex will shift the primary balancing joint away from the hip to the knees and

the weight forward onto the balls of the feet, exactly what we are trying to

prevent since the knees are not designed to rotate and that is required in the

downswing. Once the weight gets into this position, as the student initiates

the backswing, the weight is generally going to continue to move forward further

onto the balls of the feet. This will cause one to engage the improper muscles

in the lower body, namely the quads. With the weight forward and the quads

engaged, as the student transitions into the downswing, the student will be

putting unnecessary and potentially harmful stress on the knee joint and not be

able to properly engage the hip muscles necessary for stability. The knee

joint is a hinge joint. The function of a hinge joint is to allow forward and

backward movement, mainly in one plane. This means that it is designed for

extension and flexion only. With the weight on the balls of the feet, we have

now placed the burden of rotational movement onto the knee joint since the

primary balancing joint is no longer the hip, but the knee. This is a function

it is not designed to perform. Thus, we can see that it is imperative to

ensure health and safety that excessive knee flex not be introduced in the setup.

If your students question this, simply have them place all their weight on

their left over the ball of the foot and try rotating. Then, have them shift

all their weight back over the ankle and rotate again. They will be able to

easily feel how much strain is placed on the knee when on the balls of the

feet.

Proper hinging from the hips ensures that we will

not introduce any excessive curvature of the spine during setup and ensure the

weight is moved away from the balls of the feet. When one hinges from the hips

appropriately and the weight shifts back into the heels, combined with relaxing

the knees slightly, the weight is centered over the ankle joints. We use the

cue words sway forward, sway back to help students to find this position

naturally on their own. Have your students stand straight up and close their

eyes. Now, instruct them to sway forward allowing their weight to go to the

balls of their feet and then sway back allowing their weight to go into their

heels. When they've performed this motion several times, instruct them to stop

when they feel balanced and relaxed, as if they could not be easily knocked off

balance if pushed from any direction. The brain will inevitably have them

feel most balanced in the anatomically correct position, centered over their

ankle joints. In addition to the reasons discussed previously, when the

weight remains balanced in this position, the student has ensured that the large

muscles of the hips will bear the rotational forces of the swing, and the

proper muscles can be used for power and stabilization.

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint in which the ball-shaped

head of the femur fits into the cup-like cavity of the pelvis. Of all joint

structures, a ball-and-socket joint gives the widest range of movement and is

designed to allow for rotation. Given the rotational nature of the golf swing,

it is imperative that the weight be centered over the ankle so that the hip can

rotate during the swing. The final step in the setup, the slight rolling

inward of the ankles, is performed to stabilize lateral hip movement. If the

weight is on the outer portions of the foot, the hips have much more freedom to

move laterally, an undesirable trait for the golf swing. Therefore, this move

is performed in order to engage specific hip stabilizer muscles that quiet the

lateral movement of the hips. Lastly, check that the weight distribution is

approximately 50-50 between the right and left feet.

Spine: Neutral

Joint Alignment

For health and safety issues, as well as increased

rotational mobility, we want to ensure that the spine remains in NJA throughout

the golf swing. We do not want any excessive curvature of either the upper or

lower spine at setup. The spine consists of 33 ring-like bones called

vertebrae, with 26 movable components within the spine. These components are

linked by a series of mobile joints. Sandwiched between the bones in each

joint is the intervertebral disc, a springy pad of tough, fibrous cartilage

that compresses slightly under pressure to absorb shock and load. Strong

ligaments and many sets of muscles around the spine stabilize the vertebrae and

help control movement. The spine has five main regions, each with its own type

of vertebrae: seven cervical vertebrae in the neck, 12 thoracic vertebrae in

the mid and upper back, five lumbar vertebrae in the lower back, five sacral

vertebrae in the sacrum and four fused coccygeal vertebrae. Our main concerns

are the cervical, thoracic and lumbar regions.

For health and safety issues, as well as increased

rotational mobility, we want to ensure that the spine remains in NJA throughout

the golf swing. We do not want any excessive curvature of either the upper or

lower spine at setup. The spine consists of 33 ring-like bones called

vertebrae, with 26 movable components within the spine. These components are